Council of Europe and the Reykjavík Principles for Democracy « Are they enough? »

As the oldest regional organization in Europe, the Council of Europe (CoE) significantly contributed to the promotion of human rights, democracy, and the rule of law in broader Europe. Yet, in recent years, illiberalism has risen both within the CoE and in the European periphery, in line with a global trend against democracy intensifying since 2005/2006. Faced with democratic backsliding, CoE has recently adopted the “Reykjavik Principles for Democracy”, a range of principles to address current and future challenges in the region. By doing so, the CoE members tried to show they are united against Russia’s war of aggression against Ukraine and underline their commitment to democracy. But is this enough? This paper examines the policies of the CoE to address member states’ failure to respect its democratic rules and examines the effectiveness of the CoE’s toolbox at a time when democracies face a global crisis and rising military aggression.

Digdem Soyaltin-Colella, Department of Politics and International Relations, University of Aberdeen, Aberdeen, United Kingdom

Digdem Soyaltin-Colella, Department of Politics and International Relations, University of Aberdeen, Aberdeen, United Kingdom

digdem.soyaltin@abdn.ac.uk

The Council of Europe (CoE) is the oldest regional organization in Europe. It was founded in the wake of the Second World War as a peace project, built on the promise of never again. Established in 1949, the CoE is concerned with the issues of democracy, human rights, and the rule of law in broader Europe (Wassenberg, 2013). Unlike the European Union (EU) where states are requested to adopt legal and institutional reforms to comply with the Copenhagen criteria during the candidacy process, the CoE accepted arguably less democratic countries as members after the end of the Cold War, including Azerbaijan, Georgia, Russia (until 2022) and Ukraine. The acceding countries were asked to necessarily ratify important conventions like the European Convention on Human Rights (ECHR).

Since the beginning of the 1990s, the monitoring of obligations and commitments of the member states has become an essential function of the CoE, particularly of the PACE (Klein 2017, 64). Bringing together members of the national parliaments of the 46 CoE states, PACE has been the precursor in the follow-up of obligations assumed by the member states under the terms of the CoE Statute, the European Convention on Human Rights, and all other CoE conventions to which they are parties upon their accession to the CoE. In this way, the CoE aims to lock its member states into specific features consistent with the objectives of the organisation (Closa, 2013). The Committee of Ministers, the statutory decision-making body of the CoE, holds its hand to authority to suspend or expel a member state if it is found to violate the democratic principles laid down in Article 3 of the Statute (The Statue of CoE, art 8).

The CoE significantly contributed to the promotion of human rights, democracy, and the rule of law in broader Europe, enhanced minority rights and gender equality, and created a death penalty free zone. As indicated by several indices, there has been a clear improvement in liberal democracy in Europe after the Second World War (see V-Dem, 2023). As the human rights body, overseeing the implementation of the ECHR in the 46 member states, the ECtHR created a common European legal space for over 700 million citizens.

Yet, in recent years, illiberalism has risen both within the CoE and in the European periphery, in line with a global trend against democracy intensifying since 2005/2006 (Lührmann and Lindberg 2019; Diamond, 2015). Today, there is a larger number of democracies in the CoE, in which electoral competition or liberal values appear to have deteriorated. Thus, we witnessed the emergence of a hybrid form of polity, labeled in terms of diminished subtypes of democracy such as illiberal democracies and electoral authoritarian regimes (Collier and Levitsky, 1997; Levitsky and Way, 2022). Being presented as a majoritarian and bottom-up democratic alternative, illiberal democratic practices, however, have not led to higher popular participation. Instead, they have resulted in the nearly unlimited power of the populist leaders (Zakaria, 1997) and the disruption of the checks and balances. It should be underlined that the illiberal governance practices indicate broader changes in the liberal normative order.

Faced with democratic backsliding, CoE has recently adopted the “Reykjavik Principles for Democracy”, a range of principles to be respected by democratic states. By doing so, the CoE members tried to show they are united against Russia’s war of aggression against Ukraine and underline their commitment to democracy to address current and future challenges. But is this enough? This paper examines the policies of the CoE dealing with the democratic breaches in its member states and examines the effectiveness of the CoE toolbox at a time when democracies face a global crisis and rising military aggression.

1- CoE’s tools to deal with democratic challenges in its member states

The CoE statute defines clear procedures to sanction the poor implementation or the violation of democratic principles in its member states, such as expulsion and suspension. Instead of material sanctions, the CoE tends to use softer tools against its members and apply social sanctions through its well-known but rather unexplored monitoring mechanism. Regular monitoring is an essential tool of the CoE to ensure full compliance with the membership principles and to confront breaches of liberal democracy in its member states.

1.1 – Expulsion and suspension

The CoE can expel or suspend a member state if it seriously violates its rules (The Statute of CoE, Article 8). Expulsion is a politically complex exercise since it requires a two-thirds majority of representatives casting a vote and a majority of representatives entitled to sit in the Committee of Ministers (Klein, 2017). Similar to the EU that has never fully acted under Article 7 of the Treaty on EU (European Parliament and the European Commission have already referred the situation in Poland and Hungary to the Council on the basis of article 7 § 1 Treaty on European Union), CoE has never come to the point of expelling a country from membership for violating Article 3 of its statute until very recently against Russia. Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, a fellow Council member, led to the expulsion of Moscow from the CoE in 2022. This is the first time a country is expelled from the CoE.

Yet, suspension was used on several occasions by the PACE. Together with the installation of the Greek Colonels’ military dictatorship in 1967 the action of suspension had been used against Turkey when the armed forces seized control of the country in 1980 (San 1996). Turkish and Greek delegations had lost their rights to be represented in the PACE. The PACE suspended several rights of the Russian delegation (e.g. the right to vote in the PACE, the right to have rapporteurs) in 2000-2001 due to Russia’s policies on Chechnya, and again in 2014-2015 due to Russian annexation of Crimea (2014). Very recently on January 24, the PACE voted not to ratify the Azerbaijan delegation’s credentials at the Assembly, citing a failure to fulfil major commitments after 20 years in the CoE. The PACE resolution 2527 (2024) touched on the humanitarian crisis last year in the then-Armenian-populated Nagorno-Karabakh region following Azerbaijan’s blockage but also highlighted the problems related to the free and fair elections, separation of power, independence of the judiciary, and respect for human rights. Before the voting took place, Azerbaijan’s delegation itself withdrew from PACE. The suspension of the Azerbaijan delegation may resume when the conditions provided by the Rules of Procedure are met.

One has to add that whether suspension does good or bad to the prospects of a state to return to democracy is not clear. In 2014, the PACE suspended Russia’s voting rights as a sanction for the Crimea occupation. In return, Russian Federation decided, on its own initiative, not to send a parliamentary delegation to PACE in 2016. Yet, in 2019, Russia was allowed to return to the PACE even though the situation in Crimea has not improved. In 2022, the Russian Federation had claimed to withdraw from the CoE a few hours before the Committee of Ministers decided to exclude it. The Committee nevertheless decided to expel the Russian Federation for its unjustified and unprovoked military attack against Ukraine that is « incompatible » with council membership.

Similarly, Turkey, following the military coup in 1980 was suspended from its rights of representation in the PACE due to the adoption of severe restrictions on civil liberties and political freedoms. In 1984, the country regained its right to vote in the PACE after democratic elections had taken place. However, in 2016 Turkey faced another coup attempt, which was followed by restrictive measures. More importantly, the constitutional amendments that came into force in 2017 sealed Turkey’s switch from a parliamentarian regime to that of an executive presidency. The PACE decided to reopen the monitoring procedure with Turkey after 13 years because the constitutional amendments significantly expanding the powers of the Presidency were not in line with the fundamental and common understanding of democracy in the CoE. These findings indicate that the capacity of suspension measures of the CoE to reverse illiberal practices in member states is highly limited (Dzehtsiarou and Coffey, 2019; San, 1996).

1.2 – Full Monitoring Procedure

Monitoring is a tool for the CoE to verify the member states’ compliance with their commitments to the democratic principles flowing from the CoE statute per se and the fundamental conventions they ratified (de Beco, 2012; Juncker, 2006; Lawson, 2009; Royer, 2013). The responsibility of overseeing a country’s adherence to its obligations upon joining the CoE falls under the purview of the PACE’s Monitoring Committee. Being subjected to full monitoring procedure entails frequent visits by officials from the CoE, public debates in Strasbourg, and more frequent receipt of monitoring reports with action items from the PACE compared to member states that have been cleared from the monitoring list (de Baco, 2012).

The full monitoring procedure was first designed for the new member states to examine how democratic commitments are implemented. Yet, to promote its legitimacy, the PACE established a Monitoring Committee in 1997 and tried to introduce a more equitable monitoring practice that covers all member states (Klein, 2017:63). On application of an Assembly committee, its Bureau, or a group of at least twenty members of the PACE, all member states could theoretically become subject to full monitoring procedure (de Baco, 2012:173-9). Although applications were tabled for several old members such as Austria (2000), Italy (2006), and France (2013), none of them resulted in the opening of the full monitoring procedure. This was partially related with the limited financial and human resources of the PACE. Yet, Turkey as an old member of the CoE experienced the full monitoring procedure from 1996 till 2004, and then again since 2017. Under full monitoring procedure, there are currently eleven countries (Albania, Armenia, Azerbaijan, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Georgia, Hungary, the Republic of Moldova, Poland, Serbia, Turkey, and Ukraine).

In 2019, the PACE reformed its periodic reviews that apply to all Member States that are not under full monitoring procedures or involved in post-monitoring dialogues. The ultimate goal has been to generate periodic review reports on all member states over time. The Monitoring Committee used this procedure against three EU member states: Hungary, Malta, and Romania in 2020 (Alincai 2021). In 2022, the procedure was used against France, the Netherlands and San Marino. Currently, periodic reviews are carried out for Greece, Spain, and Sweden.

In its decisions to start, carry on or end a monitoring procedure, the PACE gets insights from several independent agencies such as the Venice Commission and impartial experts of the Commissioner for Human Rights (CHR) (Juncker, 2006: 6; Kicker and Möstl, 2013: 29). The Venice Commission is an advisory body of the CoE on constitutional matters, consisting of independent experts, appointed by member countries. Apart from preparing country-specific reports (mostly) requested by the PACE, the Venice Commission can also be asked by the member states themselves to scrutinize proposed legislation (Royer, 2013). The Commissioner for Human Rights also visits member states and issues reports on any question he or she considers relevant (Juncker 2006). The CHR openly challenges abuses in the member states and provides evidence to the PACE’s sanctioning decisions (Kicker and Möstl, 2013: 29).

The countries that manage to fulfil the monitoring requirements are cleared up from the full monitoring list and shift to the post-monitoring phase. At this stage, cooperation continues at a less public level. Designed as a follow-up procedure that starts one year after the closure of the full monitoring, the post-monitoring dialogue allows the PACE to re-open a full monitoring procedure with the countries that violate obligations of the CoE membership or backslide in democracy. There are three countries- Bulgaria, Montenegro, and North Macedonia- left under the post-monitoring phase. The closure of the full monitoring procedure softens the pressure of the CoE on the government and signals that the state can apply for membership in other European organizations. For example, the closure of the PACE full monitoring is strongly connected with being eligible for approval as an EU candidate country or for starting accession negotiations with the EU (Nordström, 2008:6-7).

The full monitoring procedure has achieved successful outcomes in many countries. Perceived as a penalty, or indeed, as a punishment (PACE 2013), PACE monitoring exerts social pressure by monitoring the application of democratic principles in the member states in various ways. First, the formal, structured, and regular dialogue with member states generates a sense of belonging with the community and promotes cooperative attitudes towards group norms among “friends”. The country visit allows national authorities to reflect on their ideas and submit their comments on the draft report written by peers before it is presented to the PACE. During this initial stage, the report remains confidential. Only after the governments’ comments are received, the matter is brought to PACE. This practice enables an honest assessment and a free exchange of views. Second, the PACE’s monitoring procedure is conducted in a way that generates transparency and publicity. The monitoring reports and resolutions are available on the Internet; the discussions in the plenary meetings are public. Furthermore, there is considerable media attention accompanying the PACE monitoring visits. During their ‘fact-finding mission,’ the rapporteurs contact official and non-official people and ask for explanations for the situation in the country. The PACE debates on the monitored country create a similar impact as the country becomes top on the international agenda after its democratic violations are discussed in Strasbourg (Nordström, 2008). Third, the PACE monitoring typically includes mutual evaluations on-site visits. This standards-based review, held on a regular base, invokes the impression of an unbiased and objective mechanism and as such enhances the legitimacy of the PACE (Soyaltin-Colella, 2020).

However, the politicized setting of the PACE casts a shadow on the impartiality of its decisions as the members are also parliamentarians at home. The states have an obvious interest in avoiding the monitoring procedure, and often parliamentarians vote in the Assembly accordingly. The very choice to start (or end) the monitoring procedure is a political issue. When PACE published a highly critical resolution on the “functioning of democratic institutions in Azerbaijan” in 2015 (PACE 2015) the political authorities blamed the PACE for unjustly criticizing Azerbaijan and framed the intervention as a « blatant Islamophobic move » against Azerbaijan as a rapidly developing Muslim state (IWPR 2013). After the PACE vote that challenged the credentials of the Azerbaijani delegation in January 2024, the Azerbaijani delegation again accused the PACE of exhibiting « Azerbaijanophobia and Islamophobia and being a platform to target some member states”. In their statement, the Azerbaijani authorities complained that “core principles of the PACE are exploited by certain biased groups to advance their narrow interests.” (RFERL, 2024). Similarly, Turkey accused the CoE of being ‘unjust and biased’ towards Turkey when the PACE decided to reopen the monitoring procedure against Turkey in 2017 (PACE 2017). To deal with populist accusations, the PACE should rely more on the standards-based assessments made by independent agencies such as the Venice Commission and CHR. This would provide a sounder legal base for the PACE decisions, increase the legitimacy of the CoE, and enhance its ability to have an impact on the member states.

2 – Internal and external challenges

The post-war global order, which is based on its fundamental substantive and procedural ordering principles, has promoted sovereign interstate relations and a relatively open global economy, characterized by practices of inclusive, rule-bound multilateralism, liberal democratic values, and good governance practices. The liberal order which prevailed well into the 1990s has led to a third wave of democratization and has enhanced the democracy and rule of law in a broader Europe (Huntington, 1991). The EU decided to widen its borders to the Central and Eastern European countries after the collapse of the Soviet Union. The same countries had become members of the CoE in the 1990s. Yet, in the last two decades, much has changed in the EU, in broader Europe, and the international system due to several internal and external reasons.

First, the CoE faces serious challenges in putting its own house in order amid rising disunity concerning the policies against Russia. The decision to bring back Russia to the PACE in 2019 created tension between advocates of restoration of inter-parliamentary dialogue with Russia and their opponents, who advocated that the organization should stick to its values and principles (Financial Times, 2019). Keeping Russia out would have created a new dividing line in Europe and most importantly would have prevented Russian citizens from seeking legal redress at the ECtHR, where the country alone accounted for a third of the caseload (Politico 2019). Yet it is also argued that Russia’s decision to freeze its considerable budget payments to the CoE (7% of the whole budget) in 2017 was the ‘main reason’ for the sanctions on Russia being lifted (Aldershoff and Waelbroeck, 2017; Tenzer, 2018; Glas 2019). In the end, Russia was allowed to return to the PACE in 2019 with full voting rights until being suspended and expelled in 2021 after it launched its military invasion of Ukraine.

In Turkey, the PACE monitoring backfired through the escalation of authoritarian practices (Soyaltin-Colella, 2020). The government misused the PACE’s sanctions (i.e. full monitoring) to legitimize its undemocratic measures and mobilize anti-Europe sentiments and nationalist votes. These populist policies also resulted in Turkey’s withdrawal from CoE’s Istanbul Convention on combating violence against women in 2021.

Recently, Turkey’s refusal to abide by ECtHR rulings to release Osman Kavala, a philanthropist detained since 2017 and sentenced to an aggravated life sentence, resulted in the launch of an infringement proceeding against Turkey. This could potentially see Ankara expelled from the CoE. Turkey’s refusal to implement the ECtHR’s ruling in the Kavala case indeed contradicts its obligations as a long-standing member of the CoE yet enhances the government’s anti-West propaganda (Soyaltin-Coella, 2022a, 2022b)

Apart from Russia and Turkey, Hungary, Serbia, Poland (at least until recently), Azerbaijan, Albania Slovenia also follow policies that are not in line with the democratic principles and membership requirements of the CoE. The democratic backsliding in the CoE members is highlighted by several indices.

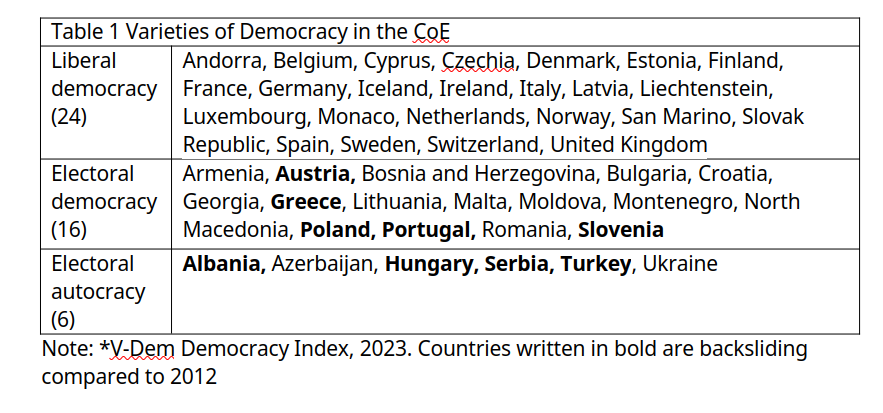

V-Dem Index highlights that 9 out of 46 member states of the CoE backslide and perform considerably poorly in the liberal democracy and civil liberties index compared to a decade ago (see Table 1). More importantly, several CoE members such as Hungary, Turkey and Serbia are no longer categorized as democracies but as electoral autocracies as they combine de facto authoritarian rule with a democratic façade.

However, democratic backsliders do not develop a policy to quit. Instead, they prefer to protect their membership rights and aim to change and transform the institutions and regulations from within. By doing so, they aim to break the dominant liberal discourse, which they claim is exclusionary and biased (Kelemen, 2020). Their alternative regime (electoral autocracy or illiberal democracy) is presented as a majoritarian, bottom-up, re-politicized democratic alternative to democratic elitism (Müller, 2016) However, in reality, it did not lead to higher popular participation or popular sovereignty; rather it resulted in corruption, rising inequality and the nearly unlimited power of the sovereign leader in many countries (Zakaria, 1997). In the CoE, these countries tend to form informal alliances and an illiberal bloc as they support each other in voting (Turkey, Hungary, Serbia, Azerbaijan, and Russia-until 2021) (Lipps and Jacob, 2022; Söderbaum et.al., 2021)

The ongoing democratic erosion damages the CoE’s role as a protector and promoter of democracy, the rule of law, and human rights in broader Europe and weakens its international credibility vis-a-vis illiberal global powers. It also raises concerns regarding the ability to effectively reverse the turn towards authoritarianism in these member states.

The challenges to the CoE’s democratic agenda are not only internal but also come from contestation from Russia and China and changing dynamics in the liberal international order. Liberal democratic principles are undermined by recent trends and developments in world politics, such as then-President Trump’s policies and diplomatic style, growing populism, the spread of authoritarianism, unilateral withdrawals from international agreements (e.g. Brexit), and the rise of illiberal global powers, most notably Russia and China, on the international stage and regional powers and alliances such as BRICS and BRICS+ (Ikenberry, 2018; Mearsheimer, 2019). There is a global de-democratization trend that hosts different processes of executive overreach, declining accountability, increased repression, electoral manipulation, illiberalism, and state capture while political pluralism, separation of powers, and rule of law—are coming under pressure in different parts of the world including promising new democracies in East Europe and Western Balkans (Lührmann and Lindberg, 2019).

Even in established democracies, far-right and populist governments tend to adopt policies that breach the ECHR. The recent Rwanda bill proposed by the conservative government in the UK, which aims to deport asylum seekers to Rwanda as a safe third country, is criticized for not being in line with the right to an effective remedy (article 13 of ECHR) and breaching interim injunction from the ECtHR regarding the removal of a person to Rwanda (Brown 2024). Yet, the criticism and condemnation resulted in calls for the UK’s withdrawal from the ECHR (Reid 2022; Donald and Reach, 2023). Together with the economic and migration crises, the changes in the wider international system have substantial effects on the CoE’s capacity to act as an influential actor in the protection of democracy and the rule of law within its borders.

3 – Reykjavik Principles for Democracy and the Future

Faced with democratic backsliding in its members, heads of states and governments of the CoE members came together in Reykjavik, Iceland at a time when Europe was in the middle of a human rights crisis. The last such CoE summit, held in 2005, had committed to “building one Europe without dividing lines” and a “more human and inclusive Europe” — even charting a path for the Istanbul Convention on combating violence against women. The Fourth CoE Summit that took place on 16-17 May 2023 in Reykjavik, aimed to ensure that the member countries reaffirm their « deep and abiding commitment » to the CoE standards and principles, including the ECHR and the European Court of Human Rights (Buyse, 2023)

The Summit resulted in the adoption of the “Reykjavik Principles for Democracy”, which is a range of principles to be respected by democratic states, such as freedom of expression, assembly, and association, independent institutions, impartial and effective judiciaries, the fight against corruption and democratic participation of civil society and young people. By doing so, the CoE members have sought to show their commitment to democracy to address current and future challenges amid Russia’s war of aggression against Ukraine. The Reykjavik Principles for Democracy have been coupled with the adoption of a recommendation on « Deliberative Democracy » (CM/Rec (2023)6. By doing so, the CoE has acted as a standard-setter and has defined deliberative democracy.

The principles read as a summary guidebook that would deepen the deliberative democracy, including not only free and fair elections but broad participation, free media, and a vibrant civil society. However, it is not clear how the CoE would enforce the Reykjavik Principles for Democracy to deal with member states with authoritarian tendencies (Turkey, Azerbaijan, Serbia, Hungary) and patterns of democratic backsliding (Poland, Austria, Greece), which are also EU members or accession countries except Azerbaijan.

In this regard, CoE and the EU can collaborate more effectively to turn their traditional relations into a more institutionalised and formal partnership. The EU has developed a comprehensive toolbox to redress the democratic backsliding in its member states, such as the Commission’s pre-article 7 mechanism, rule of law reports for all members, and the Justice Scoreboard (Soyaltin-Colella, 2022). When the threats to the rule of law became serious and systematic in Hungary and Poland, EU became more aware of the need to provide a mechanism with which to tackle member states’ failures in fulfilling the principle of the rule of law and started with making a definition of the rule of law. By extensively using the CoE’s Venice Commission’s checklist on the rule of law, the EU has introduced principles of the rule of law within the rule of law Framework – also called the pre-Article 7 mechanism. The Commission’s Framework is of substantial constitutional significance to the Union, since it provides for the very first time a public and comprehensive conceptualization of the concept by an EU institution.

The Commission’s pre-article 7 mechanism is a new instrument that takes the form of an early warning tool, whose primary purpose is to enable the Commission to enter a structured dialogue with the Member State concerned. In other words, the new mechanism is designed to precede the sanctioning mechanism laid down in Article 7 TEU. Apart from the Rule of Law Framework, the Commission has also developed the ‘EU Justice Scoreboard’ to monitor the efficiency of national courts and provide rule of law reports to track both positive and negative developments across all 27 member states.

The cooperation between the EU and CoE is based on the shared values of human rights, democracy, and the rule of law. For the last decades, the two bodies have been trying to find their common path in understanding the main values of the European heritage. In the middle of a human rights crisis, and large-scale war raging on the Continent, both organizations should look for ways to deepen their collaboration in tackling authoritarian tendencies and erosion of democratic values in their members. In the prospect of the Western Balkan enlargement of the EU, Brussels can deepen its collaboration with the CoE to track the progress in the accession countries on the way to membership.

The enforcement of the Reykjavik Principles for Democracy also requires strengthening the visibility and work of the CoE institutions, including Venice Commission’s rule of law checklist, Group of Members Against Corruption (GRECO) results, European Commission for the efficiency of justice (CEPEJ)’s statistics and ECtHR’s infringement cases. The CoE can more effectively use and visualize the data with regard to membership performance and share the records widely to create social pressure on the countries failing to fulfil membership obligations. Visual representations such as charts, graphs, and maps can make complex data more understandable and accessible to a wider audience, including policymakers, civil society organizations, and the general public. These visualizations can highlight trends, identify areas of improvement, and showcase instances where member states are falling short of their obligations. By doing so, the CoE can provide clear and accessible insights into each country’s performance and foster greater transparency and accountability among its member states. Last but not least, the top-down enforcement mechanisms could be strengthened by bottom-up procedures. In this regard, the CoE can better engage with domestic institutions, courts, justice academies, and NGOs. This could plant the seeds of democracy in the member states with authoritarian tendencies.

References

Ailincai, M.A. (2021) Who monitors compliance with fundamental values in EU Member States?: The Parliamentary Assembly of the Council of Europe might be back in the game, VerfBlog, 2021/11/04, DOI: 10.17176/20211104-131408-0.

Brown, G. (2024) Britain Is Turning Its Back on International Law, Project Syndicate, January 15.

Buyse, A. (2023) The Reykjavik Summit and Declaration, ECHR Blog. May 17.

Collier, D., and Levitsky, S. (1997) “Democracy with Adjectives: Conceptual Innovation in Comparative Research”. World Politics, 49(3), 430-51.

De Beco, G. (2012) (ed.) Human Rights Monitoring Mechanisms of the Council of Europe. New York: Routledge.

Diamond, L. (2015) Facing up to the Democratic Recession. Journal of Democracy, 26 (1):141-155.

Donald, A. and Leach, P. (2023) The UK vs the ECtHR: Anatomy of A Politically Engineered Collision Course, VerfBlog, 2023/5/05, DOI: 10.17176/20230505-204527-0.

Dzehtsiarou, K. and Coffey, D. (2019) Suspension and Expulsion of Members of the Council of Europe: Difficult decisions in troubled times. International and Comparative Law Quarterly 68(2): 443–447.

Financial Times (2019) Russia vote set to divide Council of Europe, June 24.

Juncker, J. (2006) Council of Europe and European Union: A sole Ambition for the European Continent, Council of Europe Publications.

Huntington, S. P. (1991) The Third Wave: Democratization in the Late Twentieth Century. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press.

Ikenberry, G. J. (2018) The end of liberal international order? International Affairs, 94(1): 7–23.

Kicker, R. and Möstl, M. (2013) Standard-Setting Through Monitoring? The Role of Council of Europe Expert Bodies in the Development of Human Rights. Strasbourg: Council of Europe Press.

Klein, E. (2017) Membership and Observer Status. In Stefanie Schmahl and Marten Breuer (eds) The Council of Europe: Its Law and Policies. Oxford: Oxford University Press (pp.41–92).

Lawson, R. (2009) How to Maintain and Improve Mutual Trust amongst EU Member States in Police and Judicial Cooperation in Criminal Matters? Lessons from the Functioning of Monitoring Mechanisms in the Council of Europe. Leiden: Ministerie van Justitie.

Levitsky, S. and Way, L. (2002). The Rise of Competitive Authoritarianism. Journal of Democracy 13 (2): 51–65.

Lührmann, A. and Lindberg, S. (2019) A third wave of autocratization is here: what is new about it? » Democratization 26 (7): 1095-1113.

Müller, J.W. (2016) What is populism? University of Pennsylvania Press.

Nordströom, A. (2008) The Interactive Dynamics of Regulation: Exploring Council of Europe’s monitoring of Ukraine. Stockholm Studies in Politics. Stockholm: Stockholm University.

PACE (2015) Resolution 2062, The functioning of democratic institutions in Azerbaijan.

PACE (2013) The former government of Ukraine has qualified the monitoring procedure ‘as a penalty, or, indeed, as a punishment’; quoted from PACE Doc 13304 (2013), para 392.

POLITICO (2019) ‘Ruxit’ specter haunts Russian human rights activists” May 7.

Reid, E.(2022) The UK’s anti-legal populism: UK withdrawal from the ECHR considered through the lens of the EU-UK Trade and Cooperation Agreement, VerfBlog, 2022/6/17, DOI: 10.17176/20220617-153130-0.

Royer, A. (2013) The Council of Europe, Strasbourg: Council of Europe .

San, B. (1996) The Council of Europe and Forceful Suspension of Democracy in Its Member States, TODAEI, 17:15-42.

Soyaltin-Colella, D. (2020) The EU’s ‘actions-without-sanctions’? The politics of the rule of law crisis in many Europes, European Politics and Society, DOI: 10.1080/23745118.2020.1842698

Soyaltin-Colella, Digdem (2022) The EU’s ‘actions-without-sanctions’? The politics of the rule of law crisis in many Europes, European Politics and Society, 23(1): 25-41.

Söderbaum, T., Spandler,K. and Pacciardi, A. (2021). “Contestations of the Liberal International Order: A Populist Script of Regional Cooperation.” In Elements in International Relations. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Tenzer, N. (2018) Is Russia Blackmailing the Council of Europe? EUObserver, 17 September.

Wassenberg, B. (2013) History of the Council of Europe. Strasbourg: Council of Europe Publications.

Zakaria, F. (1997), ‘The Rise of Illiberal Democracy’, Foreign Affairs, 76 (6): 22-46; Cas Mudde, ‘The Problem with Populism,’ The Guardian, 17 February 2015.